Lao Cai Wu used to bang on the door to my room—which was inside of a school—and demand that I join him. To do what? To “celebrate a little bit.” Lao Cai (tsai) Wu was always celebrating. At some point, he acquired my telephone number. The bastard. He requested that I save him into my phone as “grandfather,” one of the few English words he knew. Lao Cai Wu/Grandfather started calling me instead of banging on my door. But, sometimes I didn’t pick up because I was busy with work or because it was midnight and I was sleeping. In these unfortunate instances, Lao Cai Wu would resort to his old method of banging on my door.

I recently read The Affluent Society, published in 1958. In it, John Kenneth Galbraith talks about the wants, goals, and drivers of civilization. For the vast majority of human history, human being animals have spent their time doing things like searching out stuff to eat, creating and rebuilding shelters, and trying to exempt themselves from the food chain. Had our ancestors not done these things, they’d have been doing themselves (and us) a massive disservice. It was very much in their (and our) best interest that they find food and not die. But now, there are “stores” that sell food. We now have houses that feel hot when it is cold and cold when it is hot. The animals that used to eat us are now in cages for the enjoyment of our children. This is good, I’d say.

As “The Affluent Society” of post-war America emerged, Galbraith wondered—paraphrasing—what the fuck would we do all day? When we didn’t have to hide from tigers and pray to Tlaloc, God of Rain, what would we do? What would we prioritize? When we didn’t have to survive, how would we live?

This is the central problem of our society. Our development has outpaced our evolution. We have satisfied the basic needs that allow for us to live comfortably and focus on things other than the raw, fundamental instincts of survival. Yet, we simply refuse to do it.

Lao Cai Wu once noticed a one-dollar bill in my wallet and demanded to possess it. We were driving to a celebration somewhere in Heqing—a half-hour down the dusty, rocky, rambly road. He had never held a dollar bill before. He wanted to show it to his wife. She was pissed off at him for celebrating too much. He figured the face of George Washington would help quell the squabble.

“What’s the exchange rate?” He asked.

“Like 1 to 6 or something, but seriously, Cai Wu, just keep it. A souvenir.”

“Of course I will not!” He ceremoniously handed me a 10 Yuan note and turned around and faced forward, blissfully ignoring my attempts to return the bill.

I’ve been back in the States for a year now. I see in our society the ills that plague every society: inequality, prejudice, anger, division, poverty. These will exist so long as people walk the earth. We can only mitigate the tangible, physical manifestations of these things. Or maybe we can make our prejudices and inequalities “merit-based” instead of founded on uncontrollables. But, we cannot and will never erase them. They are the double-edged sword of freedom and, I guess, of our human minds.

But, what really shocks me sometimes about my home is the way we prioritize. I say we to include me. It’s this oft-fucked up prioritization system that drives people to depression, to anxiety, to fear and loneliness, to killing themselves—to do things that should clearly be at odds with what we want from the human experience.

Our development has outpaced our evolution. In 1016, a misstep might have led to being eaten by a wild beast. Back then, it was existentially advantageous to be anxious. The beasts weren’t in cages yet. In 2016, a misstep might lead to an angry email from your boss. These are not the same thing. But I think we think they are. I think we are hardwired to think they are. Or, at the least, fear them similarly.

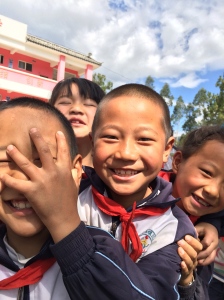

Life in the village of Sanzhuang was informal. Simple is perhaps another way of putting it, but unfortunately simple is a misperceived word. So, informal. An undeniably large portion of this was choice—lack thereof. When you are a farmer, you are often confined to your lifestyle. Same is true for the teachers at the school. It was a steady job—an iron rice bowl, as they say. You know what you’re getting. You know you’ll be stable. You know you’ll never be rich or poor. You know you’ll have enough to survive. So, you can devote your free time to enjoying your life.

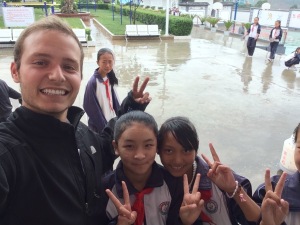

I often felt conflicted telling my students what I thought I was supposed to tell them. Study hard, make it out, go get yourself a better life. It was not that I believed that the village of Sanzhuang was Utopia. I did find people to be enormously giving and particularly content, but there were plenty of problems there. Nah, it was that I realized the danger of telling people—especially young and impressionable people—what exactly the pinnacle of self-actualization is. It was not that I didn’t believe that kids should strive for success and all that shit. No, it was because I didn’t want that lie on my conscience when the kid studied hard and didn’t make it out. I didn’t want to know that somewhere, some young adult in a village in rural China thought they sucked because they didn’t have a flatscreen in their house. But, I did it anyways.

Contentedness and satisfaction are fundamentally at odds with the way we have constructed our country. Consumerism and capitalism don’t jive with fulfillment. The best advertisement for food is hunger. The best advertisement for shelter is rain. The best advertisement for safety is being shot at. But, what happens when those evolutionary needs are taken care of? We cannot stop needing. Companies have to sell us things. So, society creates the illusion of necessity. And when our physiological obligations are no longer an issue and our stomachs are full, we look for some other void to spend our time trying to fill. But, we don’t have our hunger and our cold-rained-on head to tell us what that’s supposed to be.

Recently, in a discussion with a friend:

“Dude, you’d think at this point Kia’s wouldn’t even exist. Every car should just be Beamer-level quality. Everyone should have a Beamer.”

“Dude, if everyone had a Beamer, Beamers wouldn’t exist.”

This is our modern paradox. This is what we got from escaping the epic shittiness of starvation and destitution. See, stuff is relative. It’s a zero-sum game. There is, of course, always better. And, where there is better, there is worse. So, even once we achieve what we think we need in the relative world of stuff and success, we stumble across the unfortunate surprise that we have new things to strive for. We promptly readjust our desires.

But, hunger is not relative to anything but a stomach. Neither is shelter. Neither is happiness or enjoyment or satisfaction. Those things are not zero-sum. We have enough resources that no one should be hungry. We have enough of the relevant neurochemistry that everyone can be happy, and not at the expense of anyone. But, not everyone can have the best job. Not everyone can have the Beamer.

When we submit to the illusion of necessity, we’re really fucking ourselves. We’re whack-a-mole-ing. If we lose, we feel bad. But, we can’t ever win once and for all. Another illusion always pops up.

So, we have reinvented the notion of survival, relocated our bodily needs to our minds. Achieving our coveted place (because there are only so many places) on the hamster wheel requires us to keep spinning. We get in early and stay late, or else the tiger will maul the fuck out of us. We get the flatscreen, or else we die of starvation.

Here’s where I say that there is nothing wrong with being caught up in all of this. At the very least, striving for success and stuff gives us something to do. Plus, I love my home. There’s plenty of good in this country. But, it bums me out when people get tricked into thinking the value of their existence depends on manufactured notions of happiness and success. Maybe that’s why there’s so much angst and anger in our 2016 country. Lots of people were told that the success of their lives and their personal happiness was tied to their economic wellbeing. That’s why they’re supposed to be angry with the leaders who took their happiness away and mailed it to factories in Cambodia. That’s why they’re jumping in with the guy who’s supposed to make their happiness happy again. But, chances are probably pretty good that tossing out a few million people and stopping them from trying to come back and take away our happiness is not going to be very effective. Remember, it’s not a zero-sum game. Everyone can have it!

When I think about what I miss most from Sanzhuang, I think about people and places. I think about my noodle spot and the daily novelty of being a laowai in a rural Chinese village. What I really know I miss most, though, is the informal way of life. Maybe it was the impermanence of the experience. Maybe it was the character of the place—easygoing, casual, not too serious about itself. But, in any event, I always felt like the priorities were appropriately arranged.

Lao Cai Wu was always making an excuse to celebrate. But, his excuses were always a joke. Cheers to Mao. Cheers to the youth. Cheers to that chicken. Cheers to whatever. He would laugh as he made his toast. Wink, wink. We don’t need a reason, you and I. One time I asked Lao Cai Wu why he celebrated so much. He probably thought about it for a few seconds.

“Why not?” He probably said. “I like it. It’s a good thing. Right?”

Sanzhuang Village

Sanzhuang Village

Old woman returning from work

Old woman returning from work